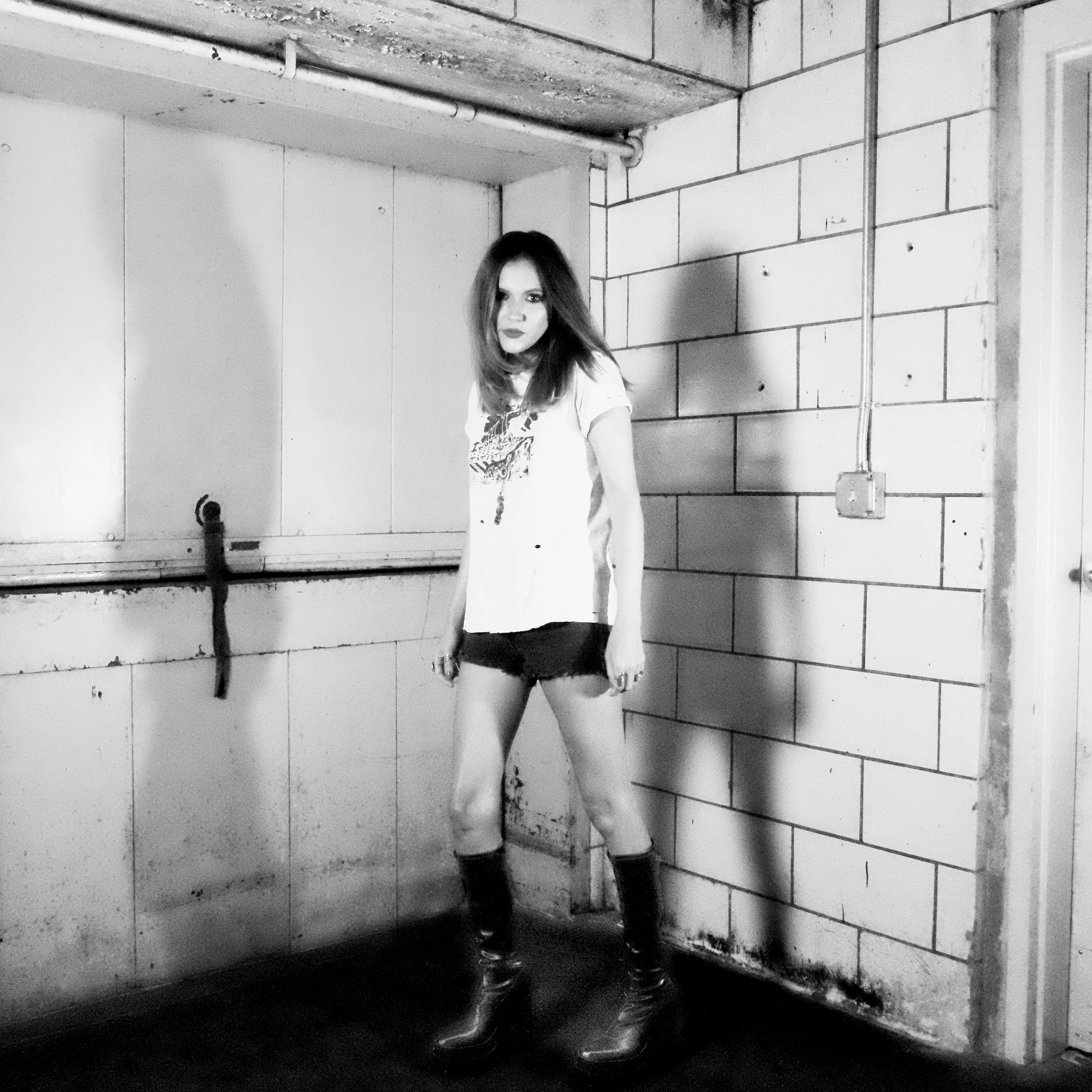

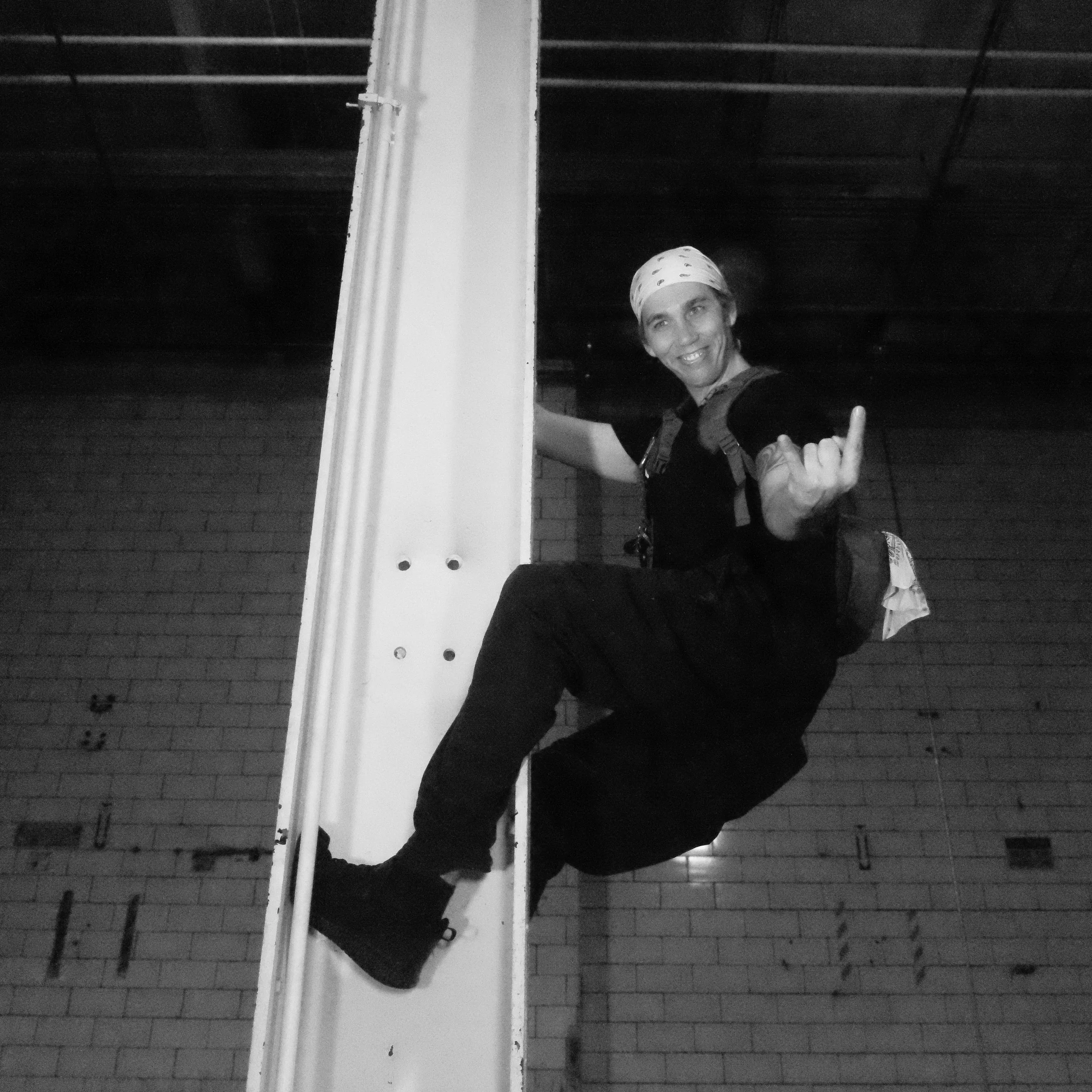

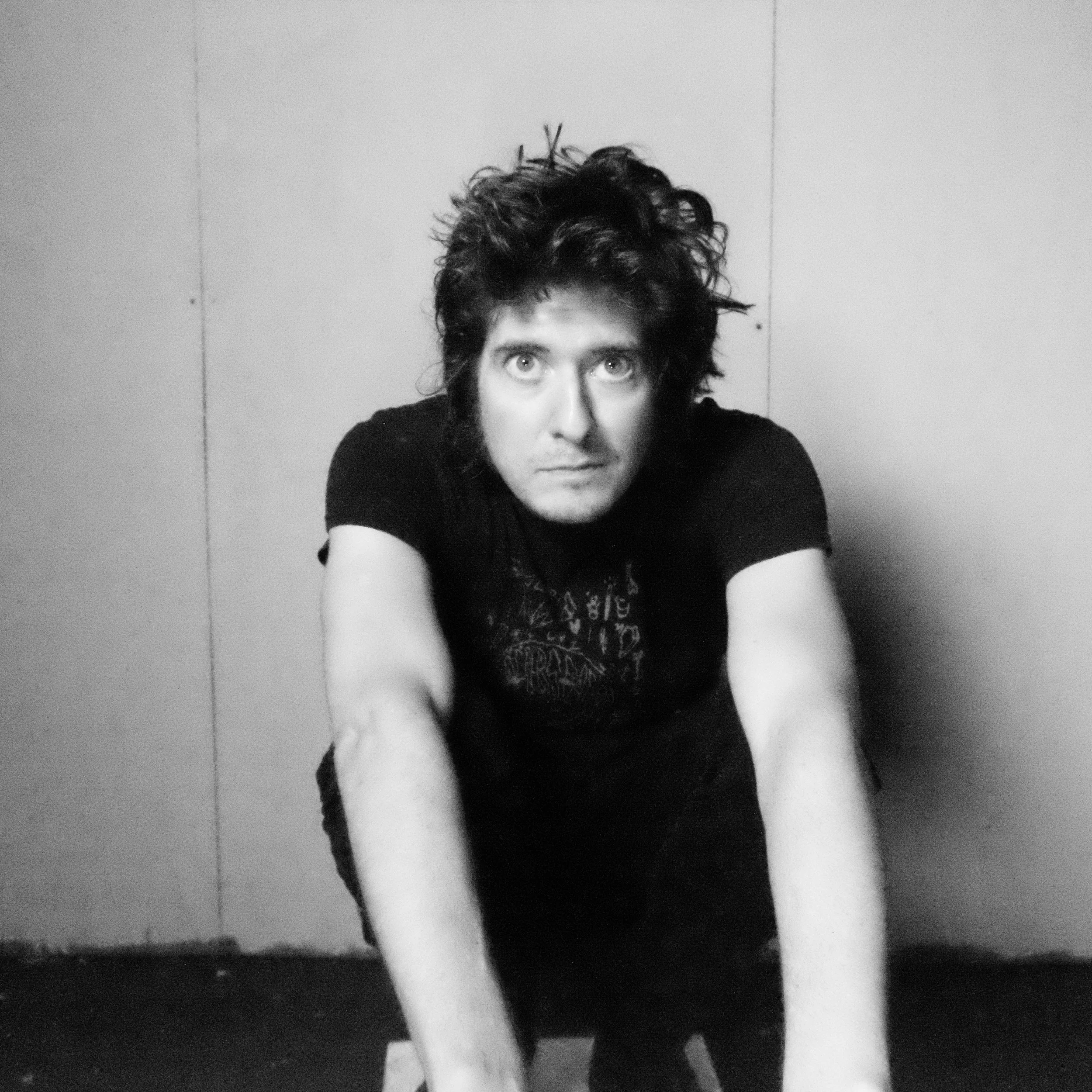

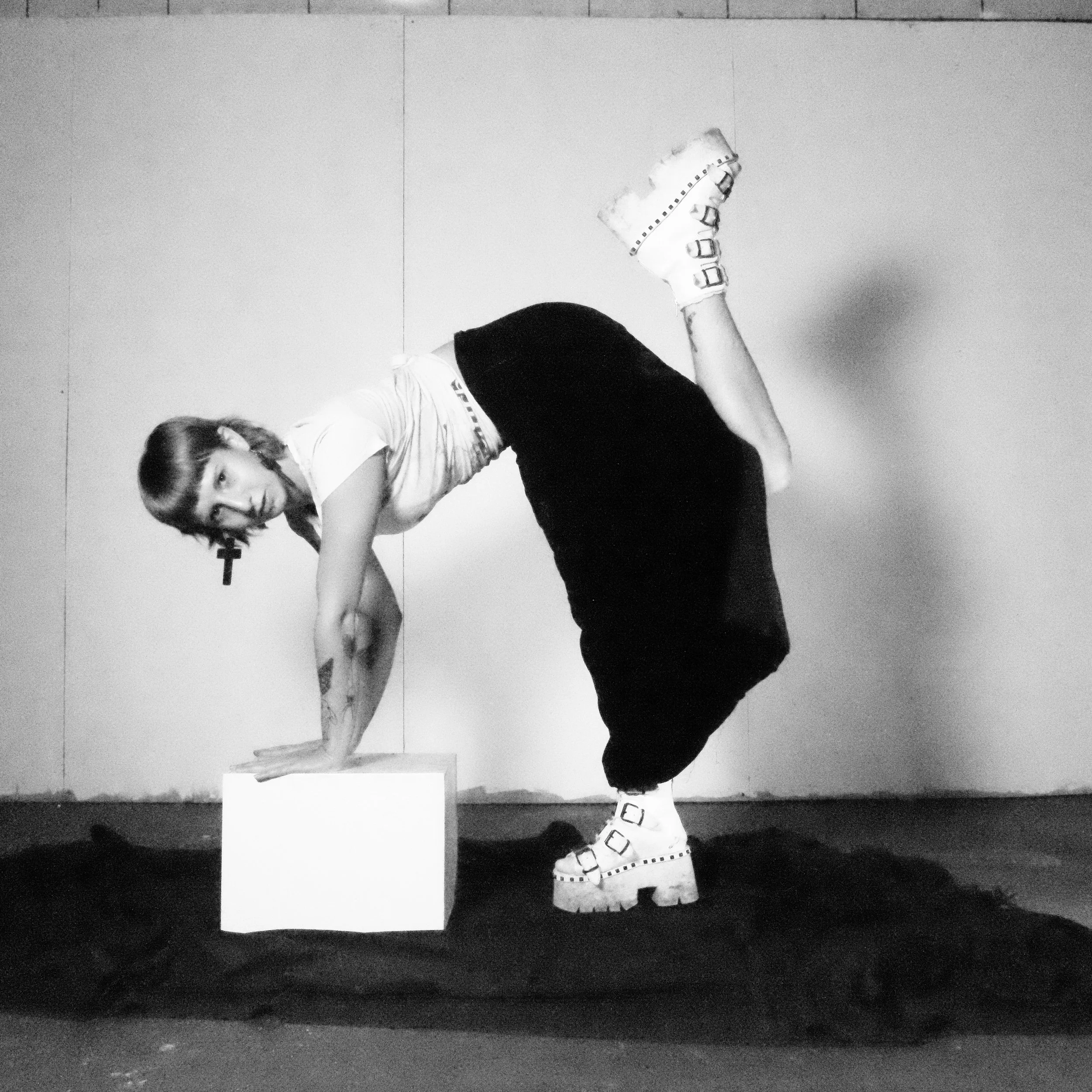

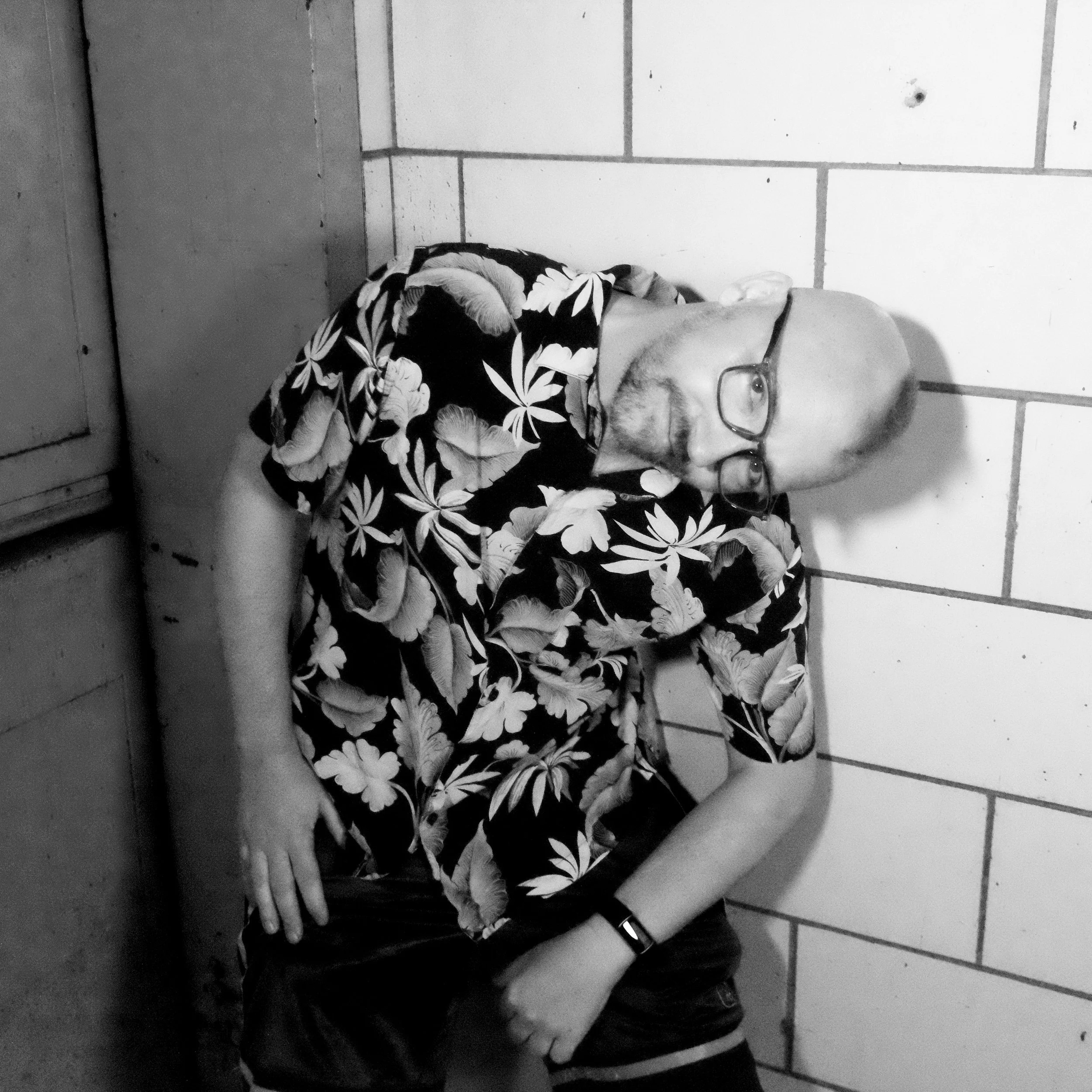

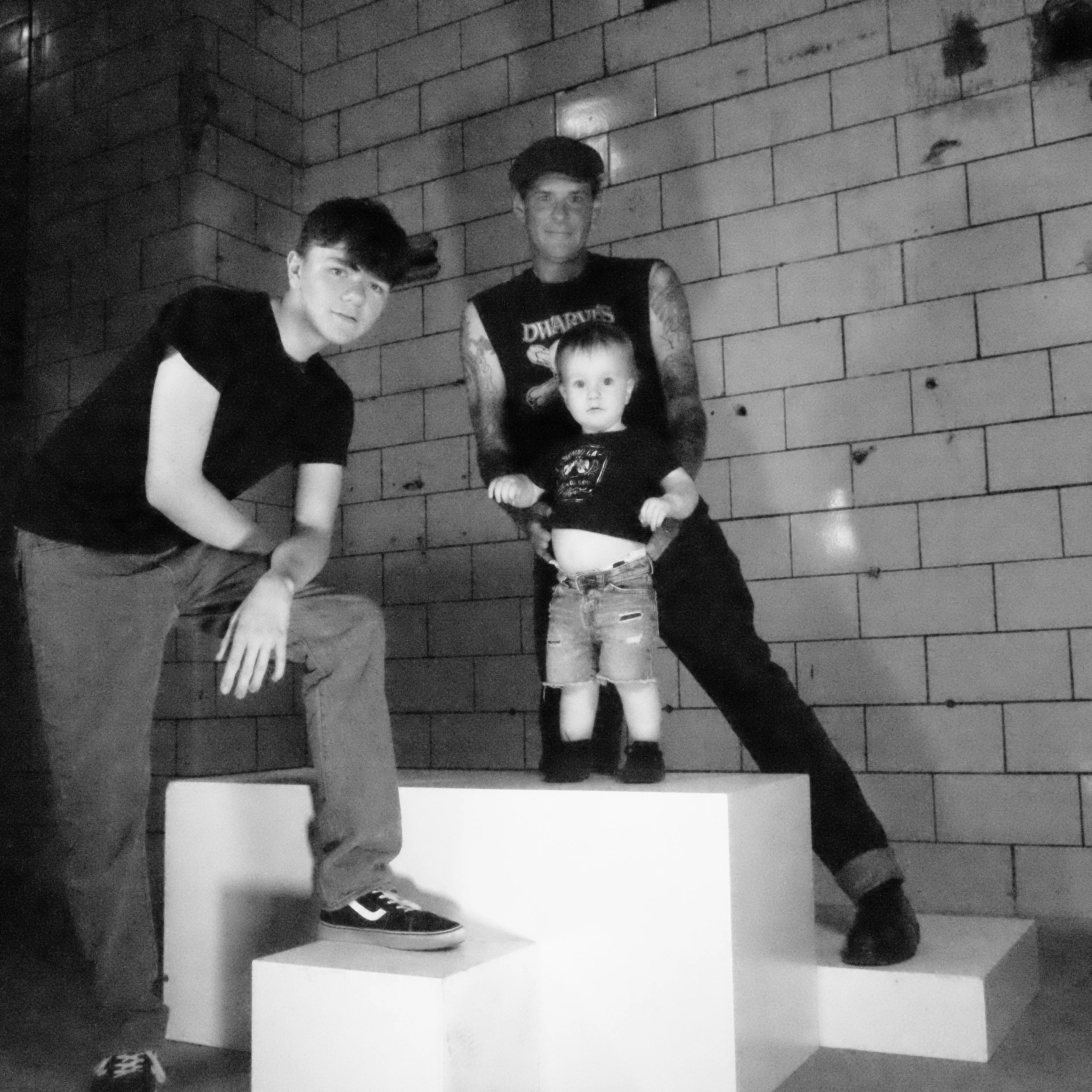

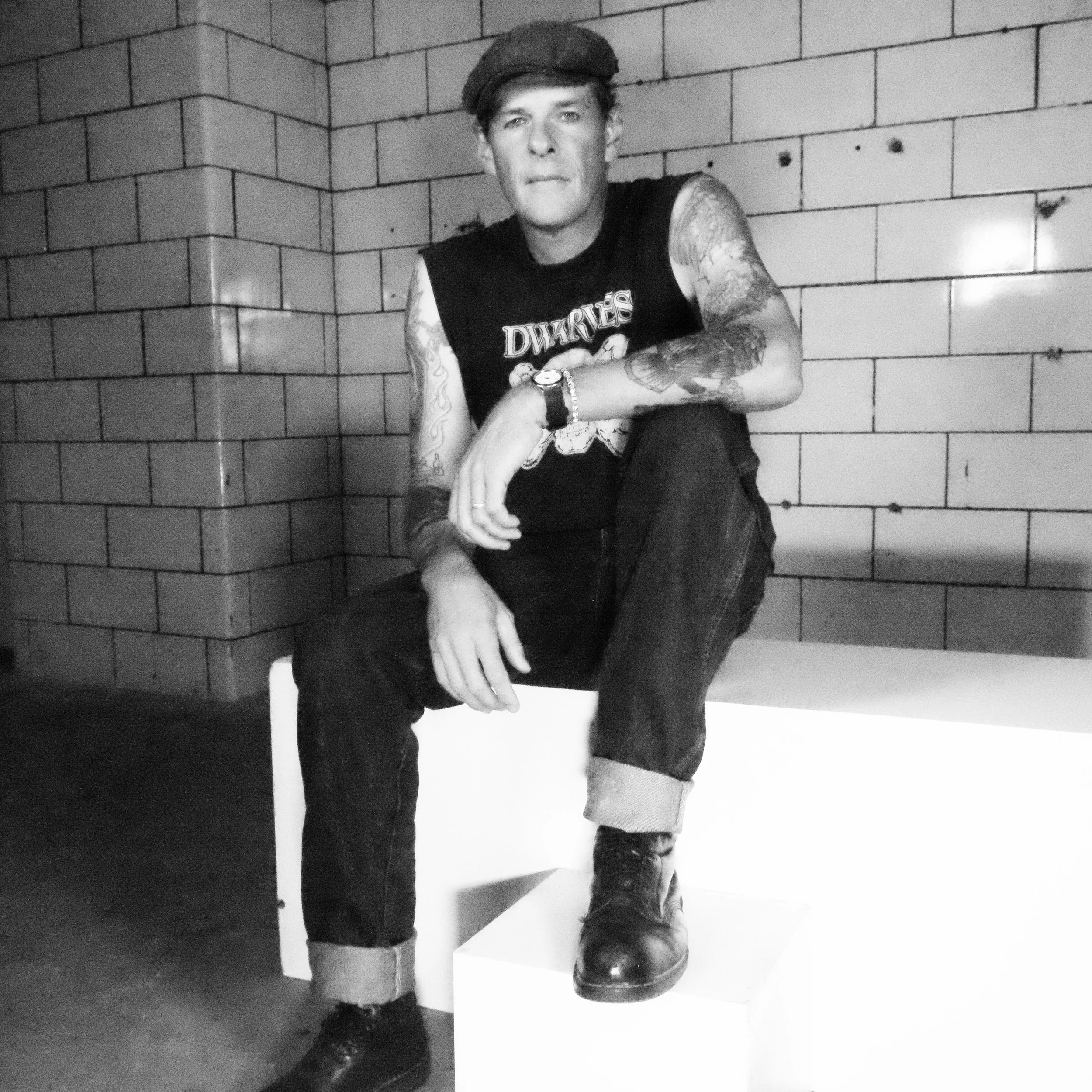

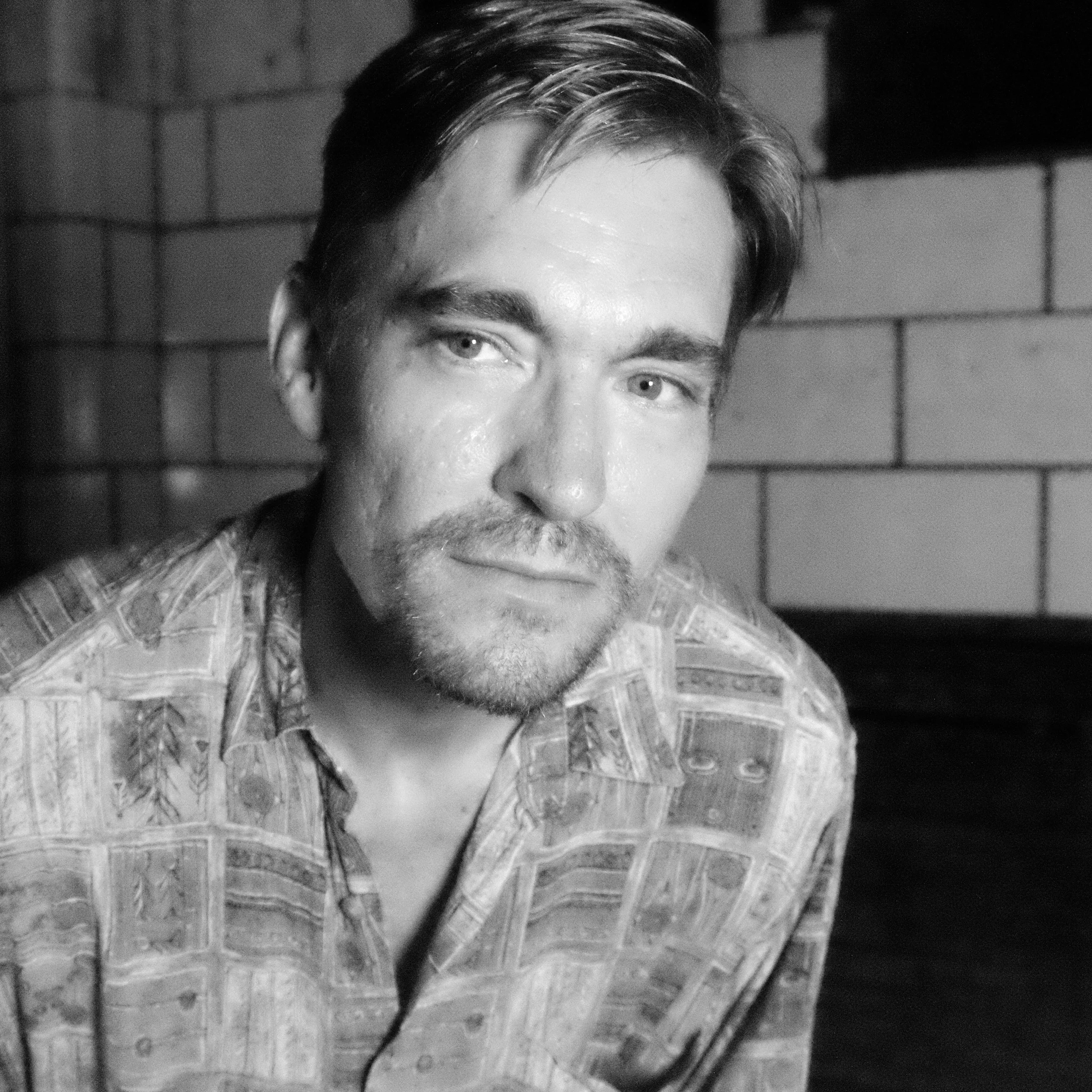

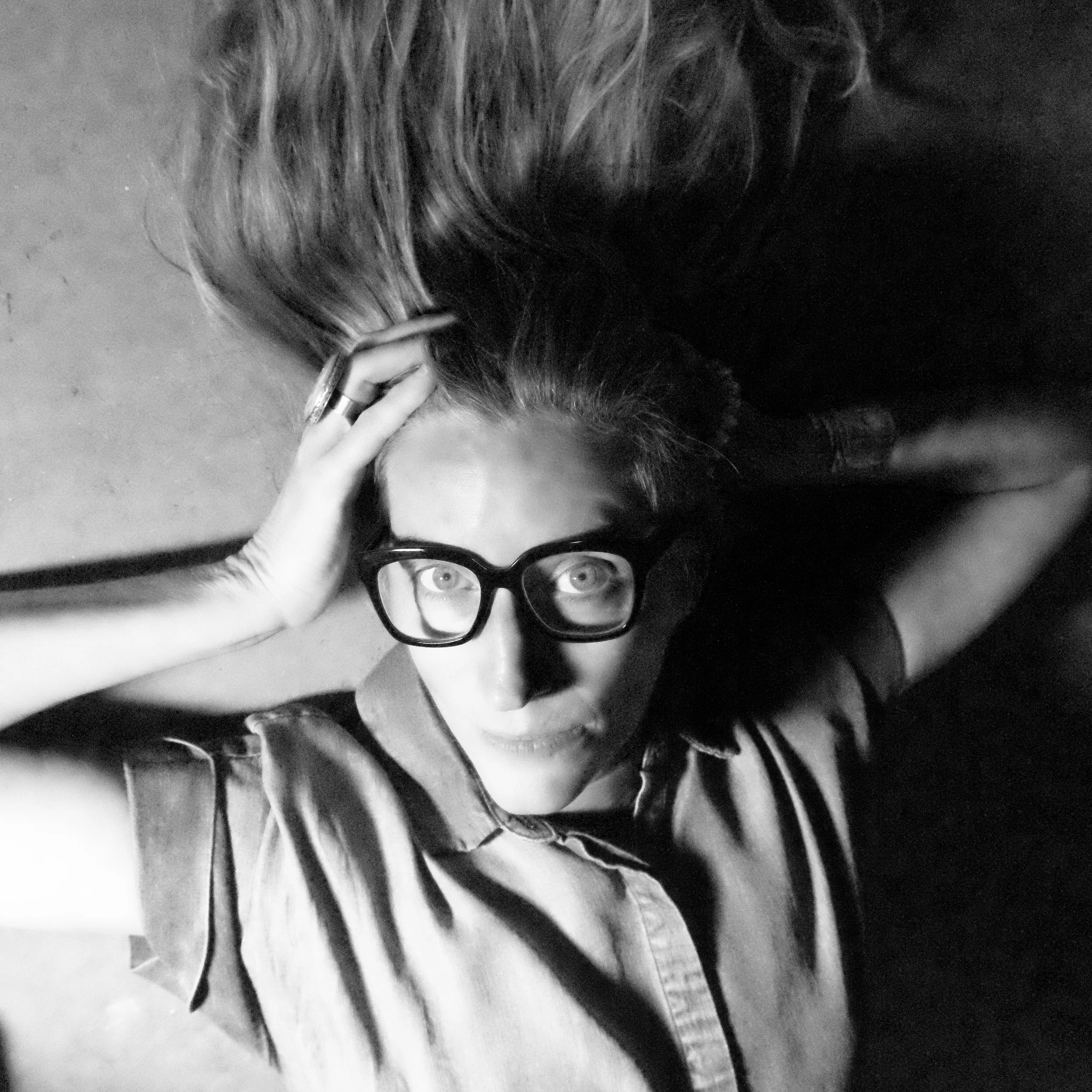

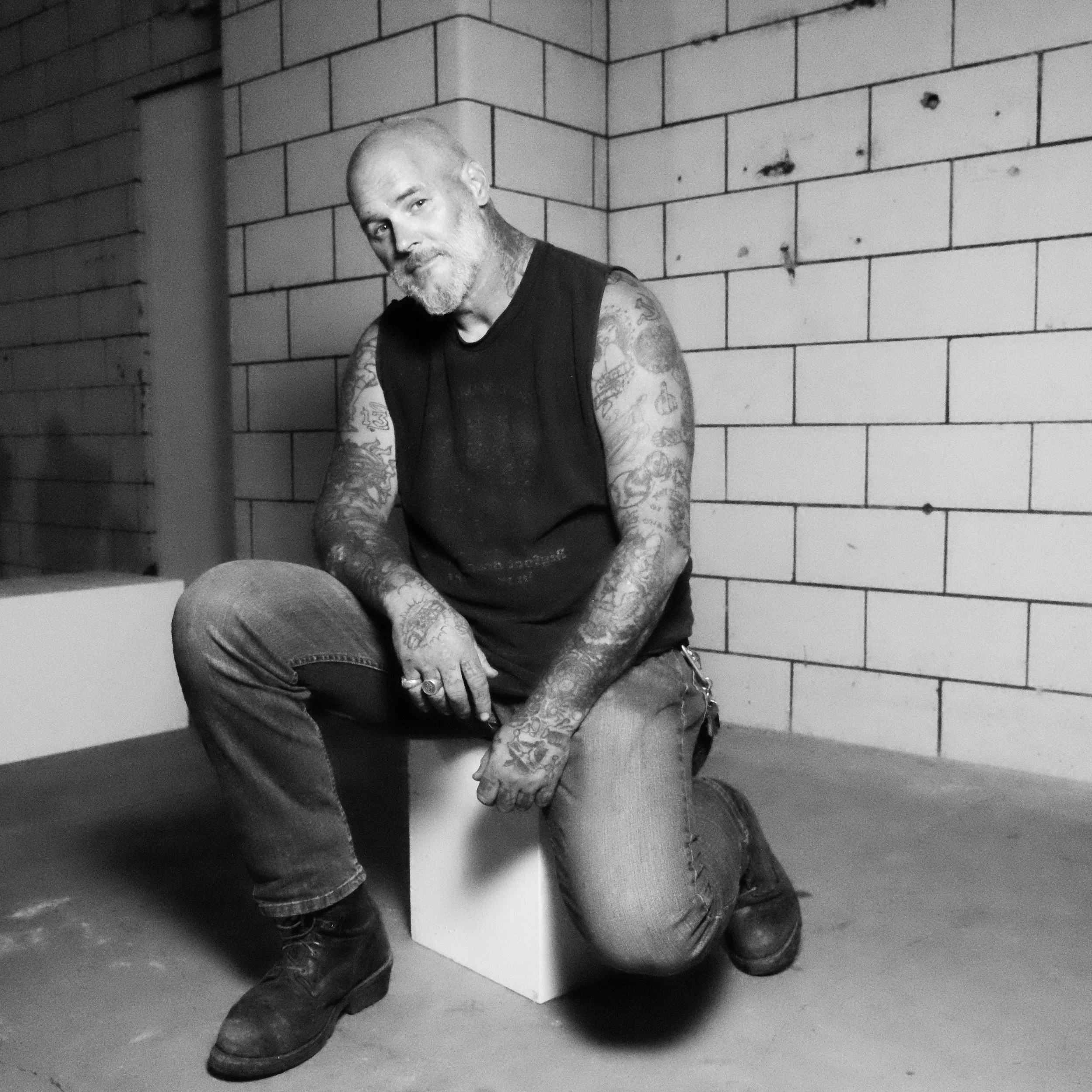

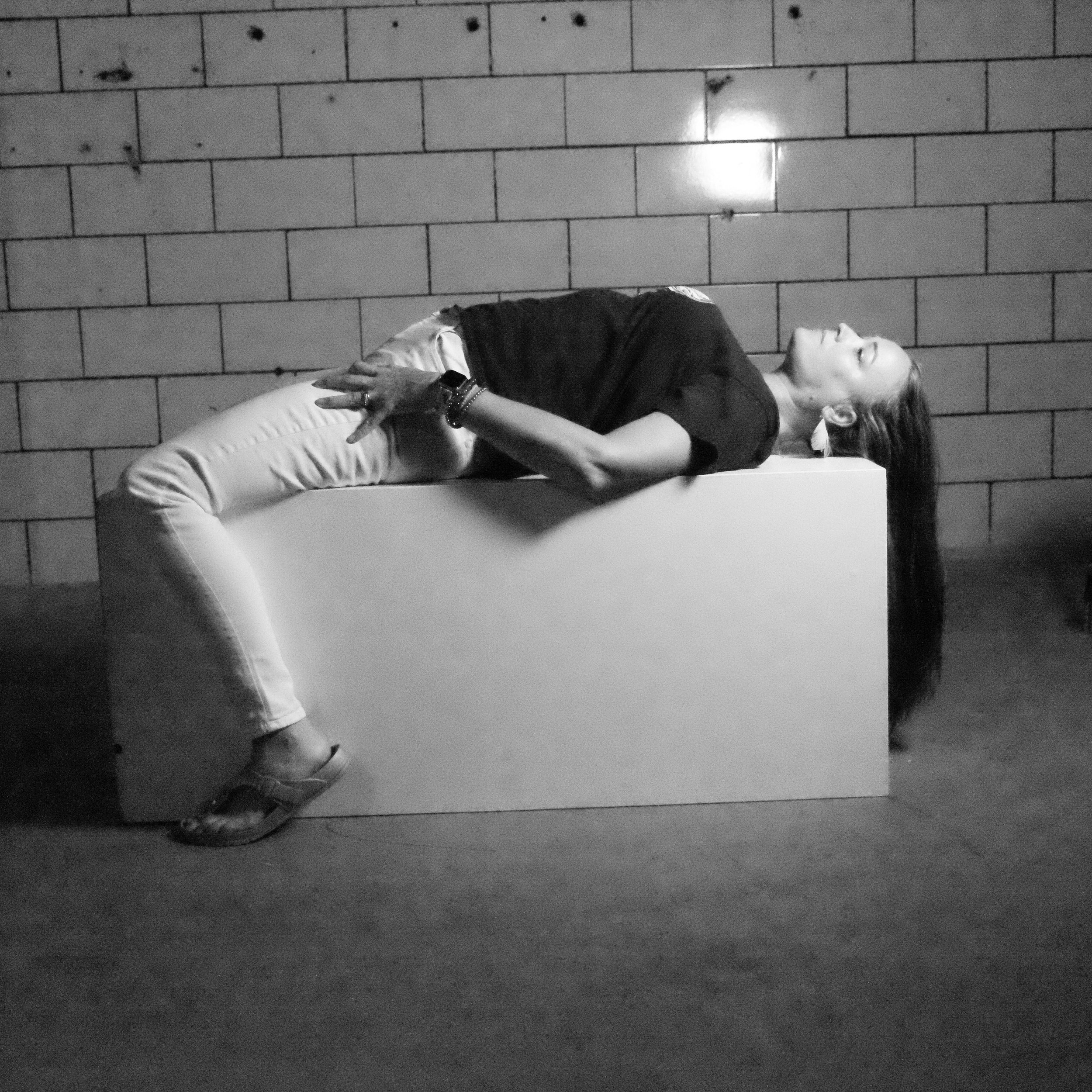

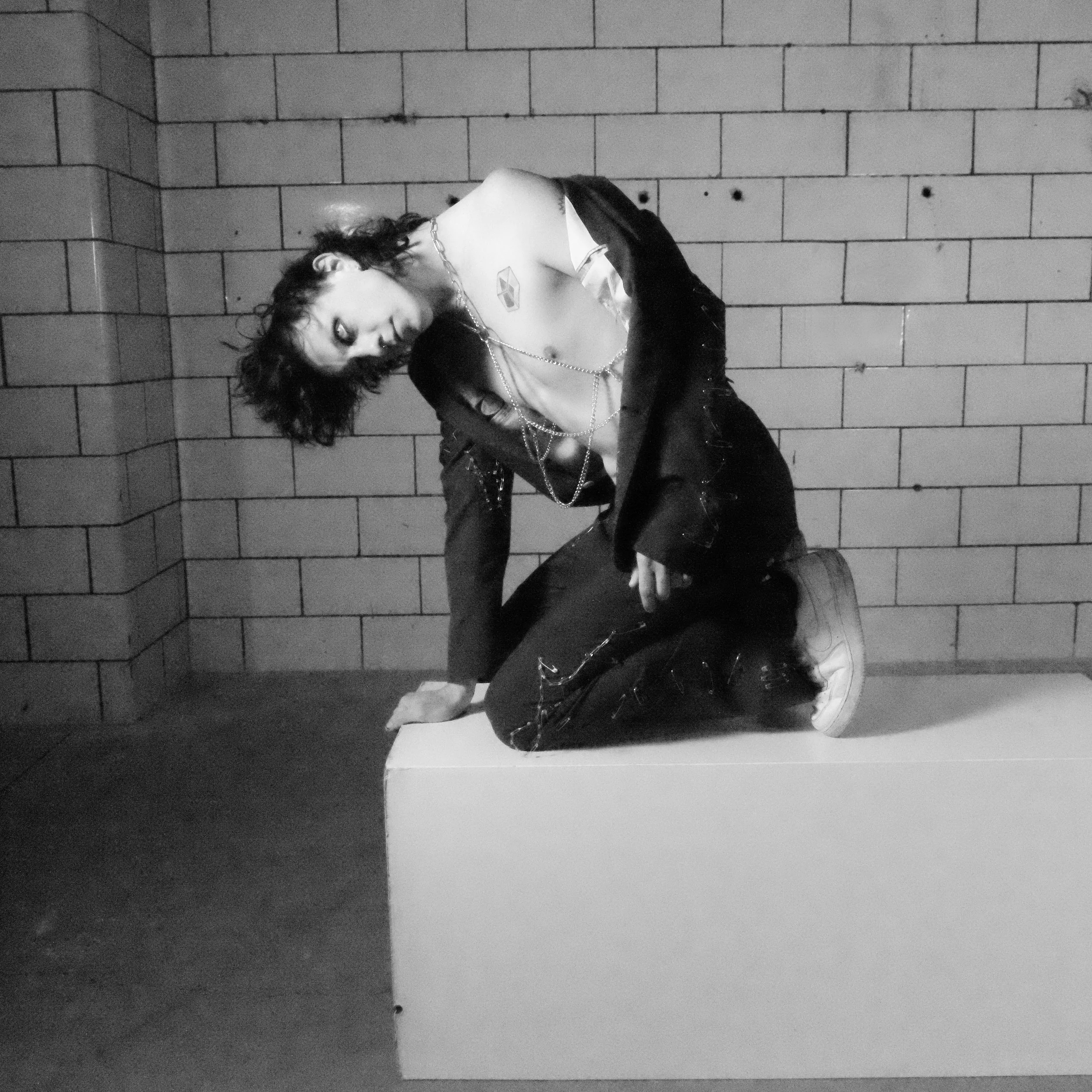

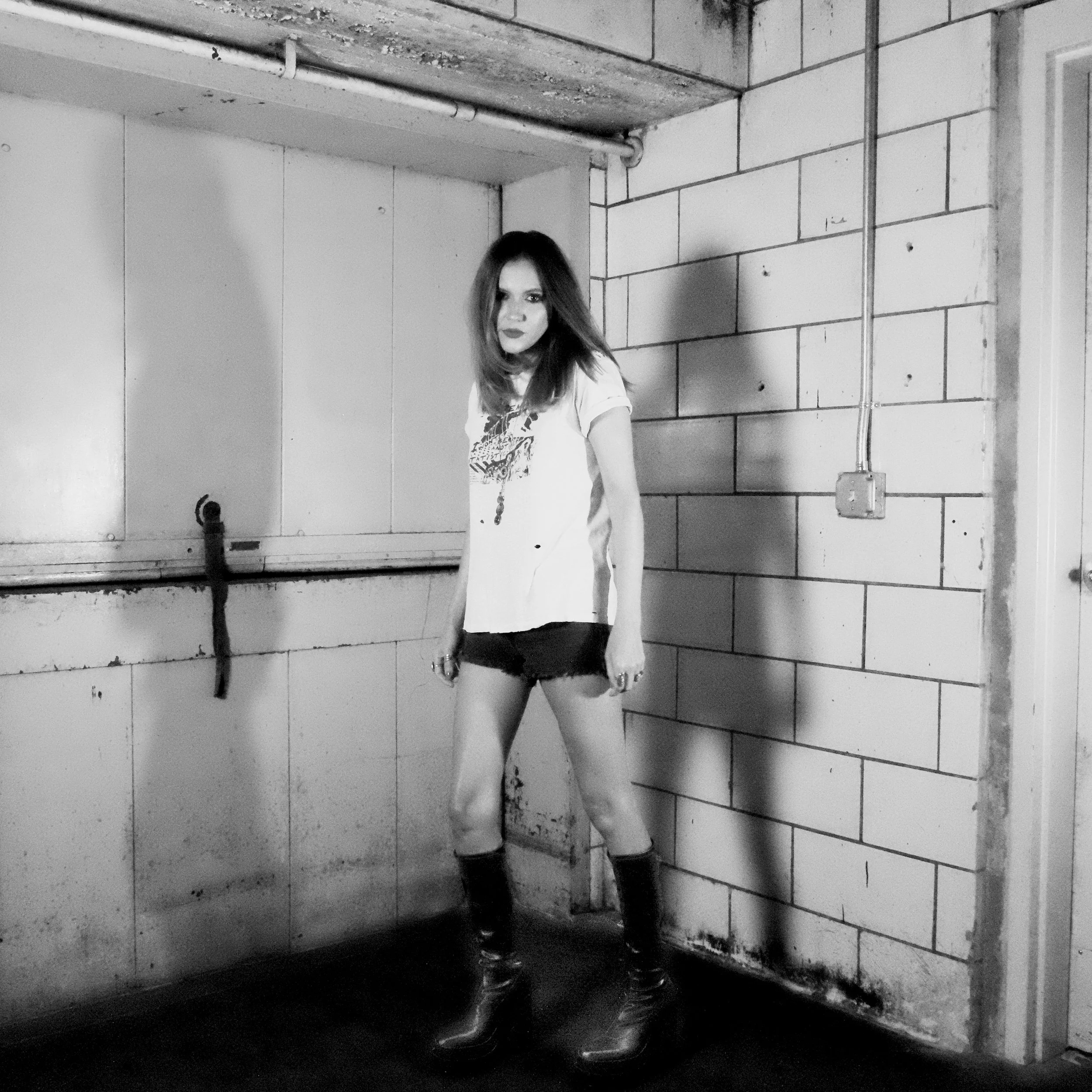

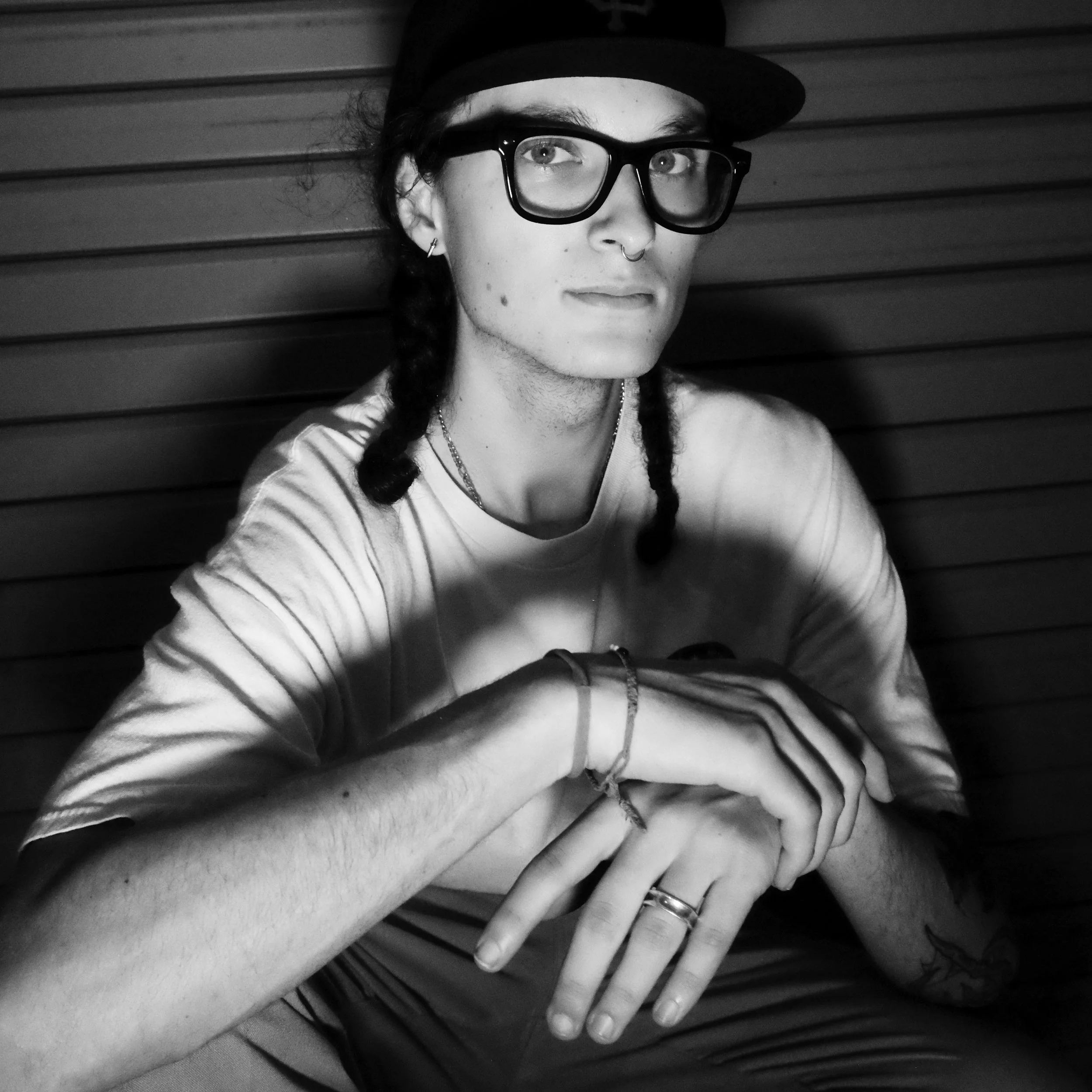

Cagey, a cagey bunch. Julia didn’t rightly have time to give a shit what kind of introspective, apprehensive, sardonic, or psychotic tendencies we might have, it was time to see what these people’s faces looked like in this big weird room. The high volume and fast pace she takes portraits at doesn’t allow for tangential creative butterfly chasing or small talk. She meets a stranger, oftentimes rigid as the military and as quiet as the woods, and she has about seven minutes to either capture something interesting about them or just — not, so her communication with her subject must be warm and respectful enough to win their trust immediately, but succinct enough to keep things moving should her first couple ideas trip, and this does sometimes happen. But cagey folks appreciate this type of efficiency. Or maybe I just do. Regardless, there are a lot of photos in this book, they were taken in a shockingly short window, and many more were taken that you don’t see. Efficiency. After she and Dan went back Up There, I noticed something happening. There was a renewed sense of community, mobility, and drive across our alliance of riffraff Down Here. Our people were just feeling better. It might be because that big back room at the art center was lit with the same type of Soviet-white, buzzy, hanging fluorescent cones as most of the old high school gyms around here, bringing back memories of picture day, or because it was the first time a bunch of us had seen each other since Covid, or maybe it’s the tickle of energy in the air as we get ready to weather one of our downswings, like the gasp of air before diving underwater. I don’t know. But I just keep talking to people that just keep tracing the spring in their step back to one of those four days.

To say Julia is a photographer is to say Cool Hand Luke is a film about a competitive eater— you’re technically correct, but you missed what some would consider the interesting part of the flick. Community Art is kind of a dork-ass term for the type of community service required by whatever my religion is called. I don’t know if Julia is comfortable with this terminology. Community Art, I mean. Not because of the nomenclature, just because I don’t know if she knows of the depth of her impact, we do appreciate it though. I know it’s not just me on this one.

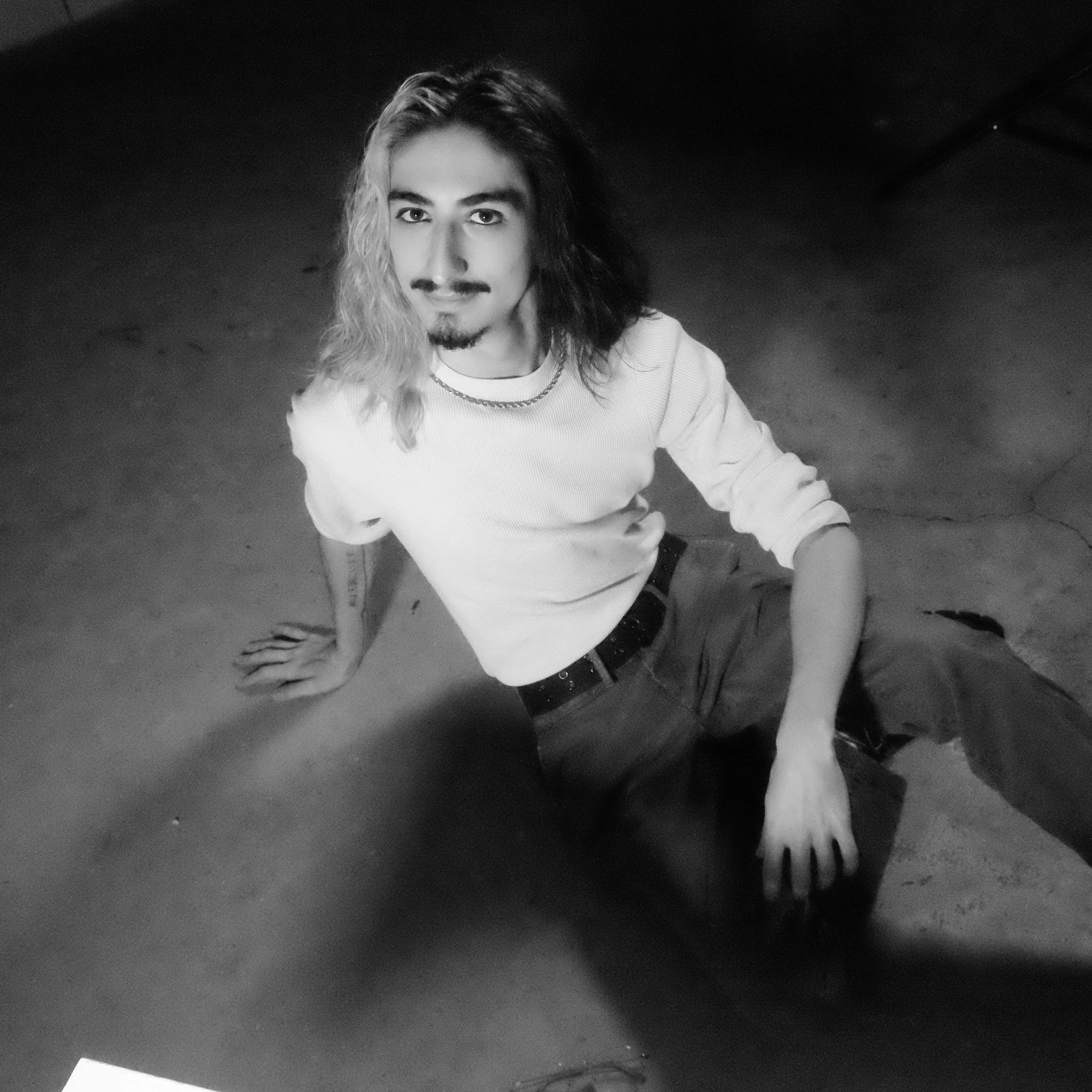

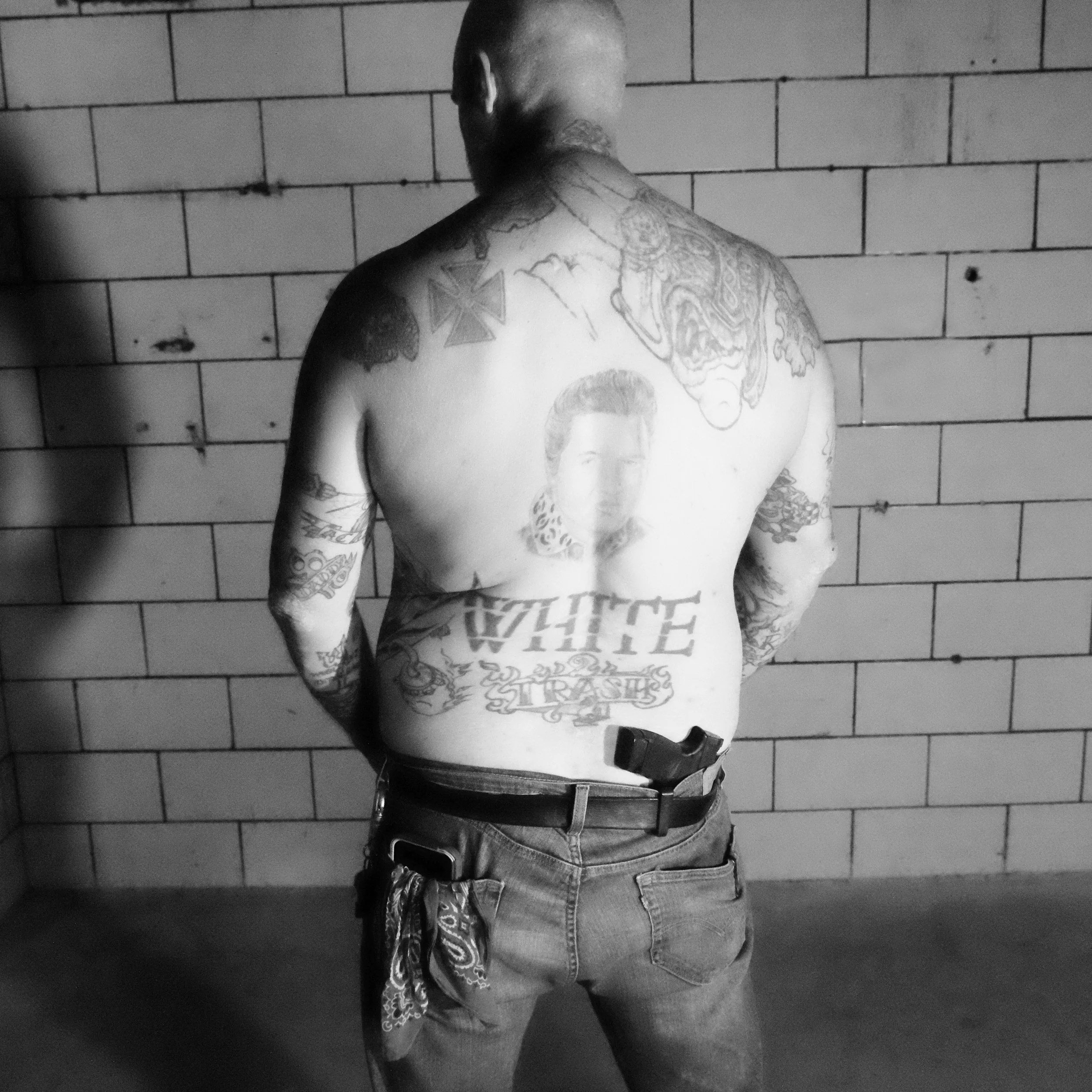

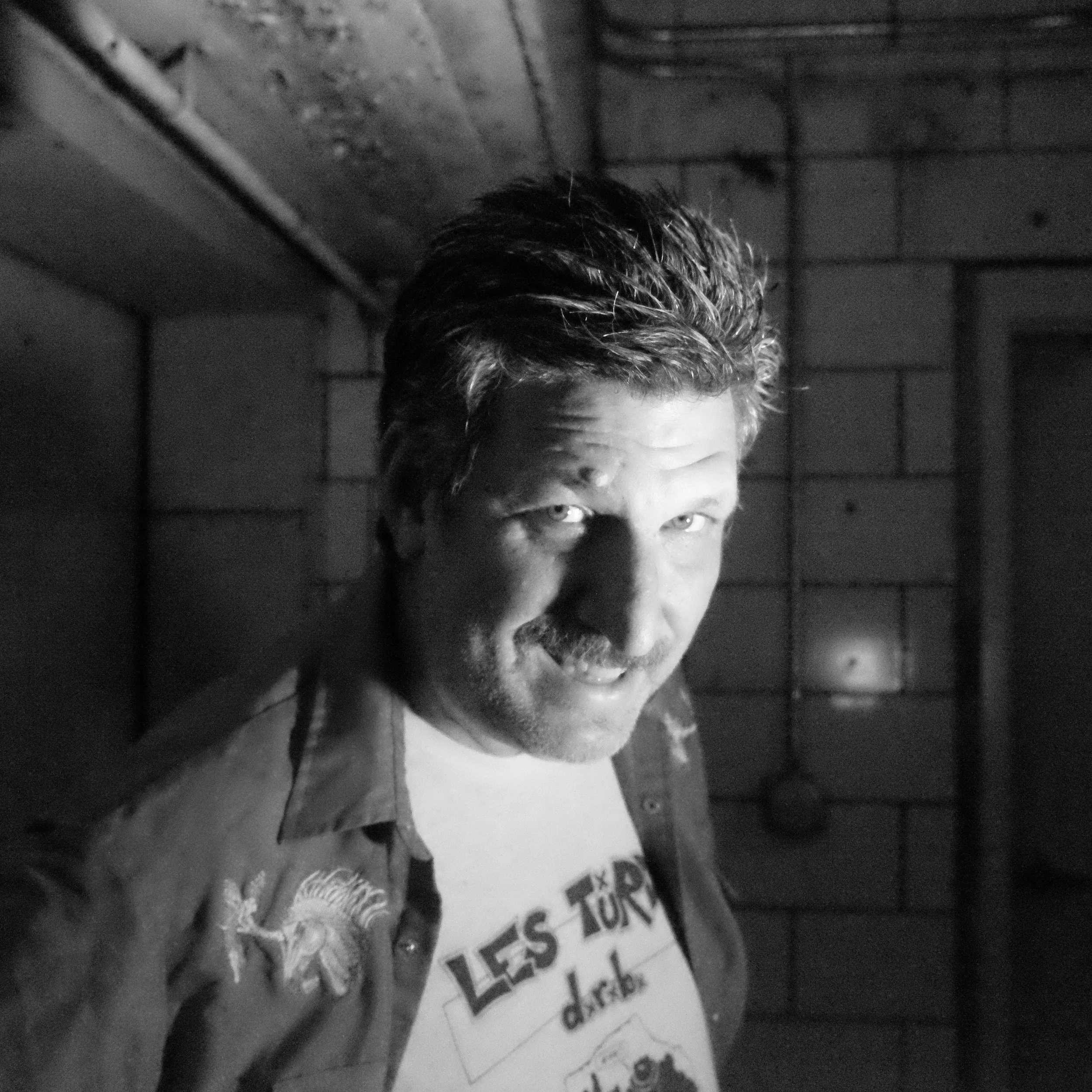

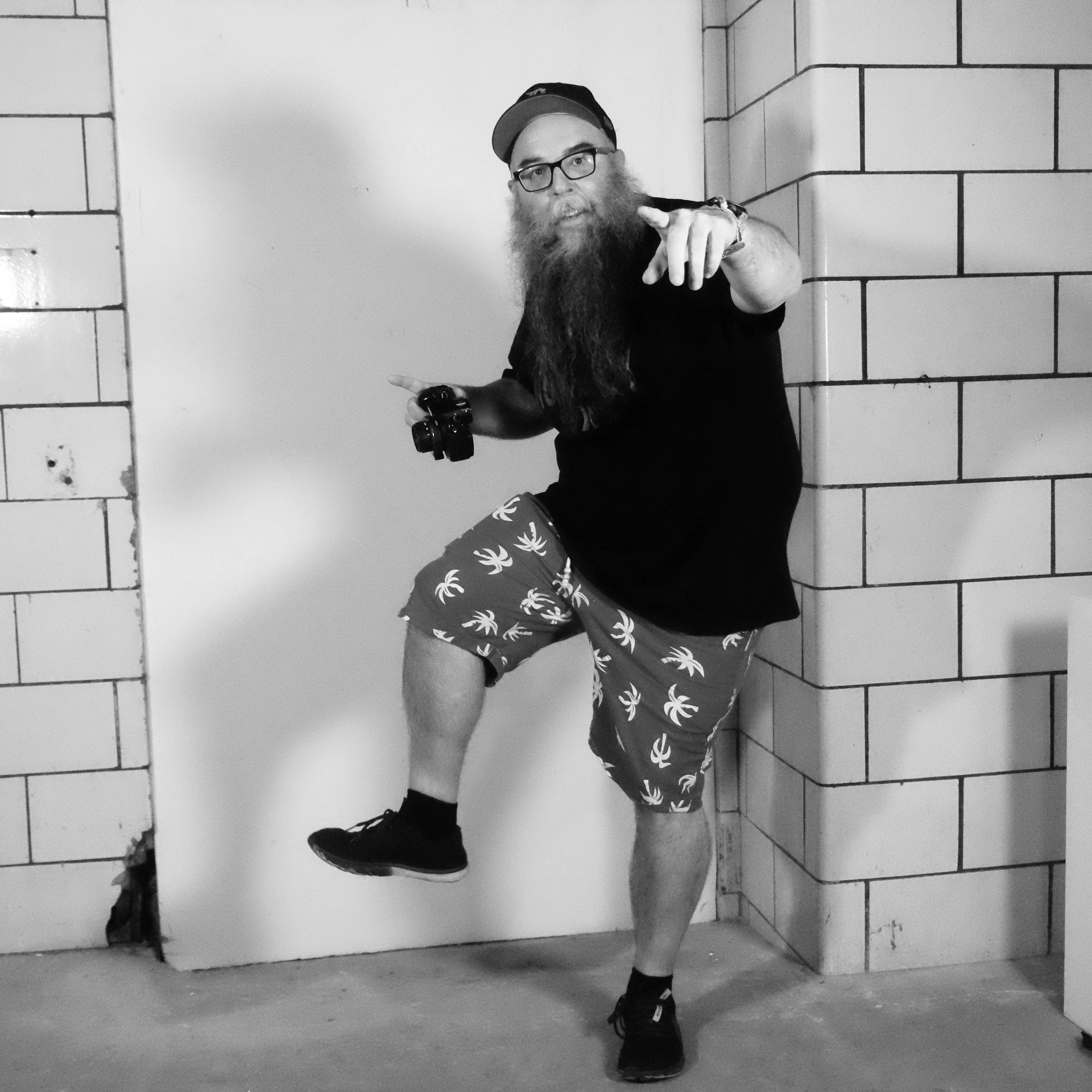

JAMES BLACK, musician

A HURRICANE PARTY is a social event held by people in the coastal Southeast. When the waters are warm, the weather starts to whip up, and dense bands of thunderstorms form. People stay with their friends for a few days and bring supplies such as radios, first aid kits, food, and drink since there’s a good chance the electricity will go out. This town knows a good party opportunity.

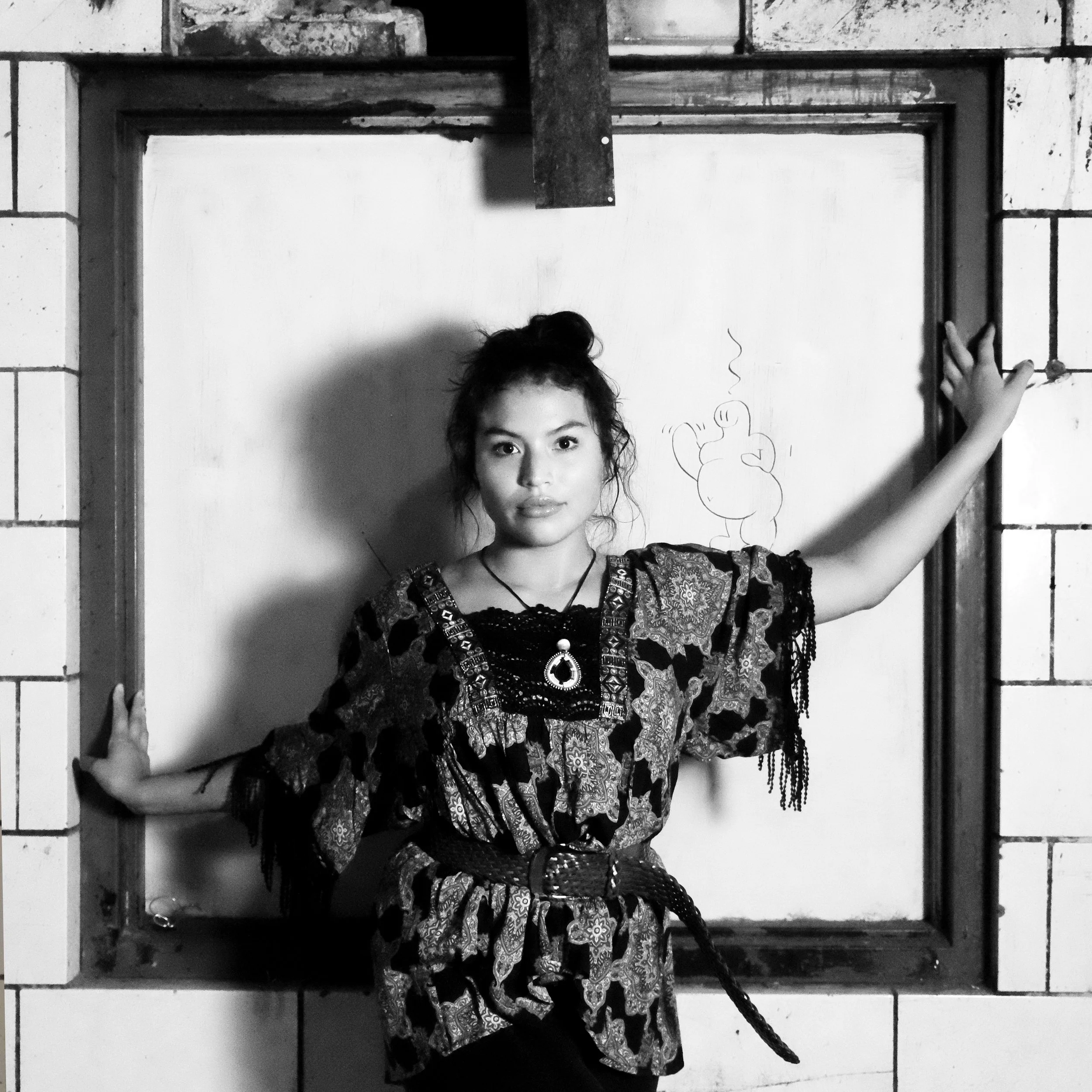

As I write this, it’s Fat Tuesday, the last day of Mardi Gras in Mobile. For weeks, the streets of downtown have been filled with marching bands, floats, and a colorful parade of humanity. Alongside the parade route sits the Alabama Contemporary. The Mobile Press-Register used to print their newspaper twice daily in this space, and the floor in the back room still holds the stains and marks of ghost machines.

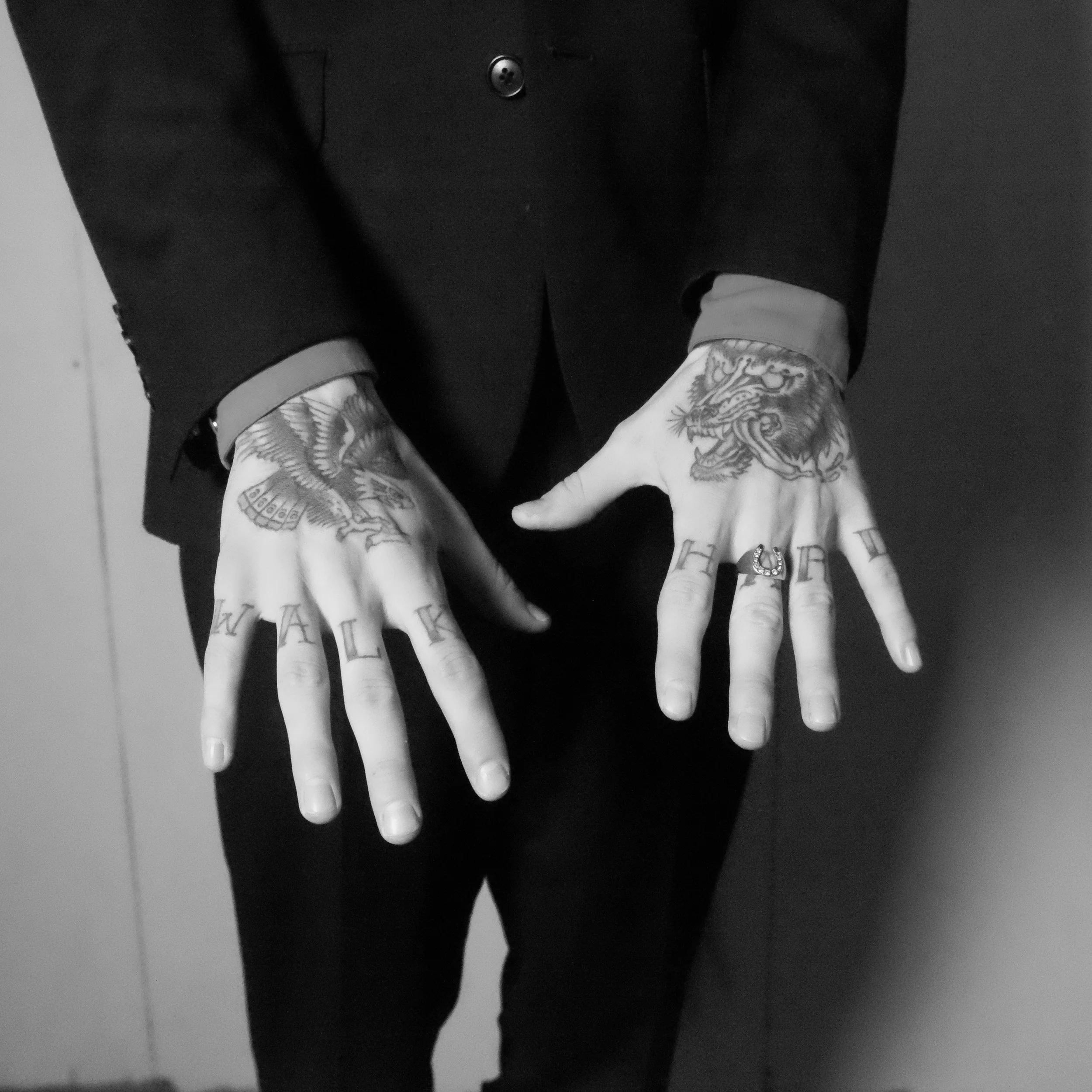

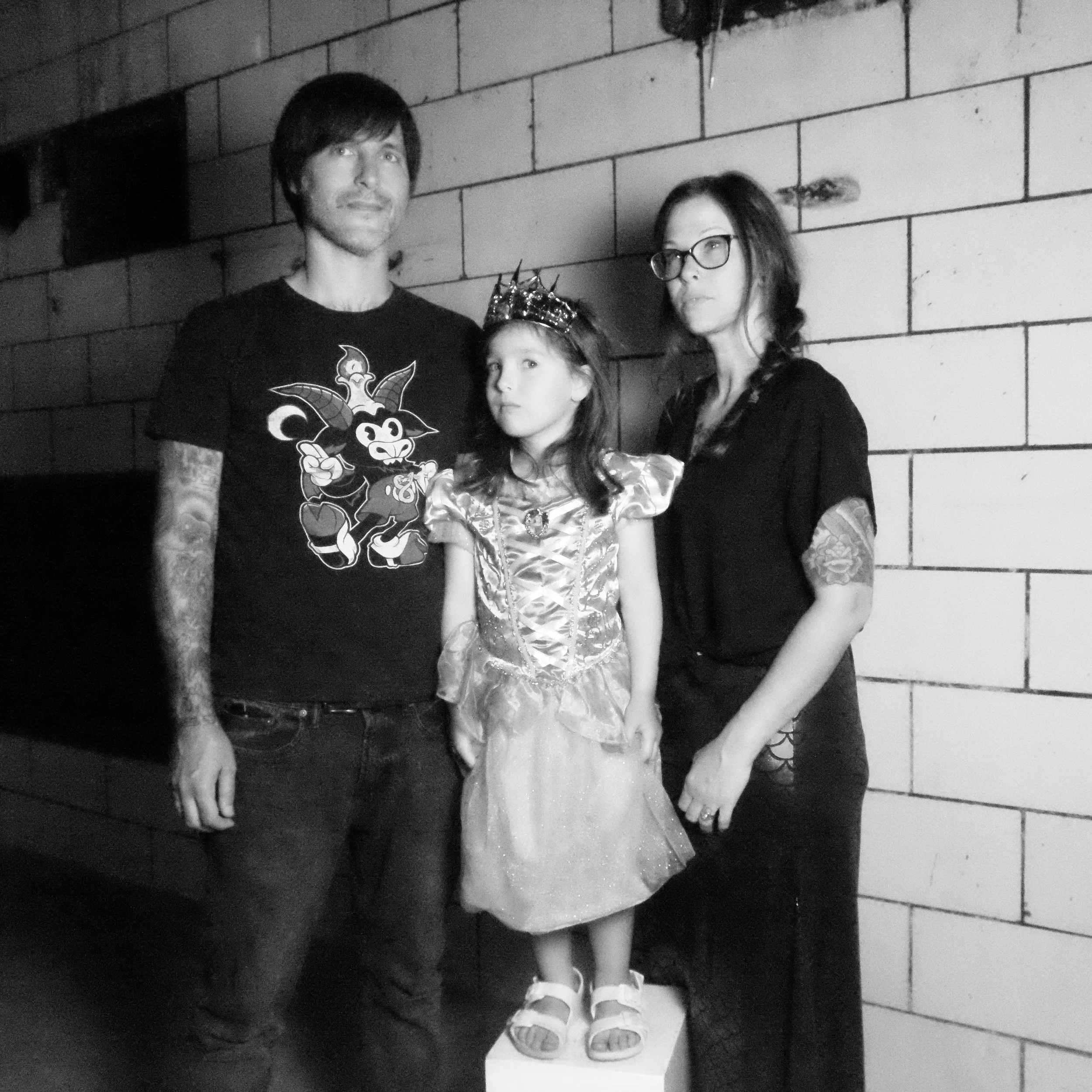

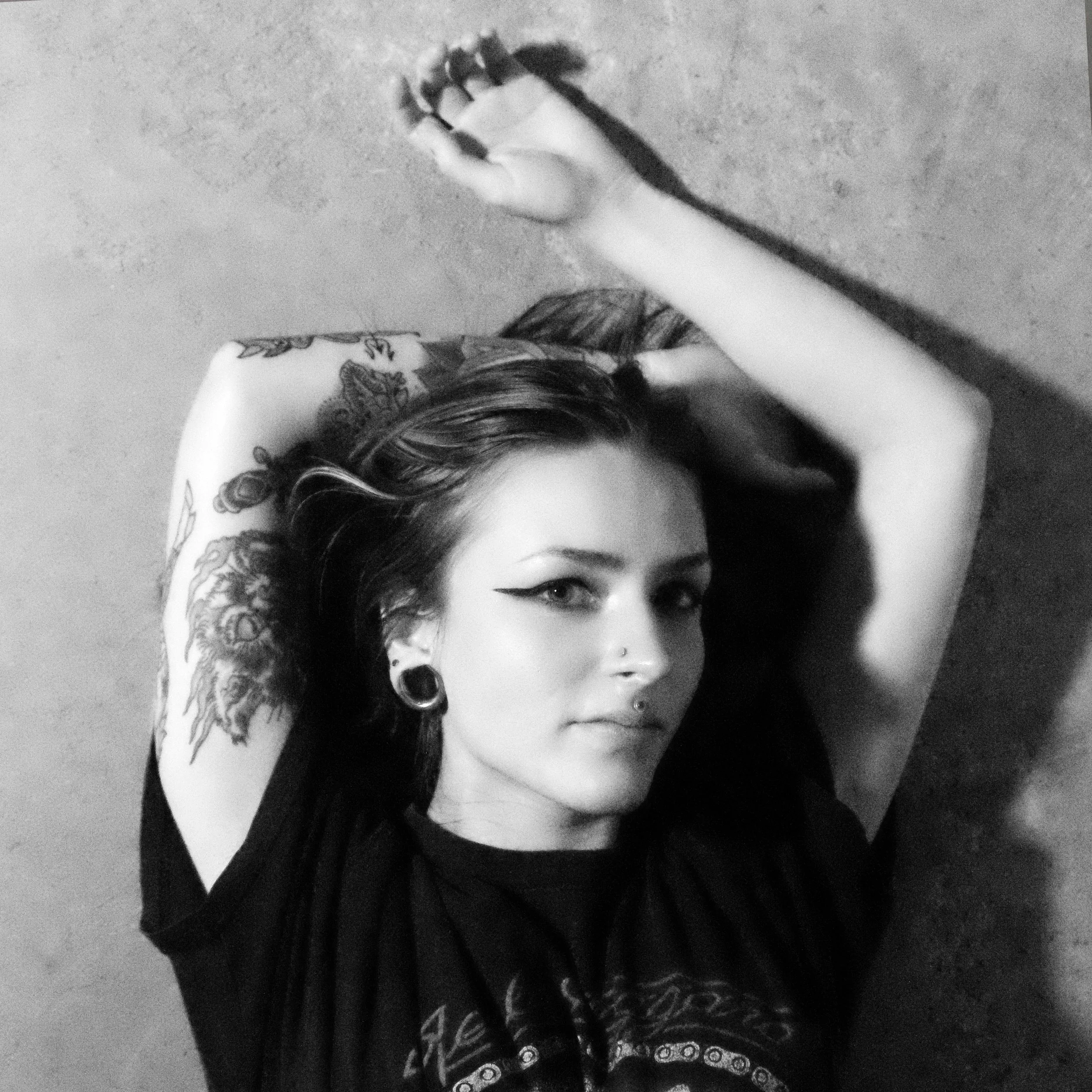

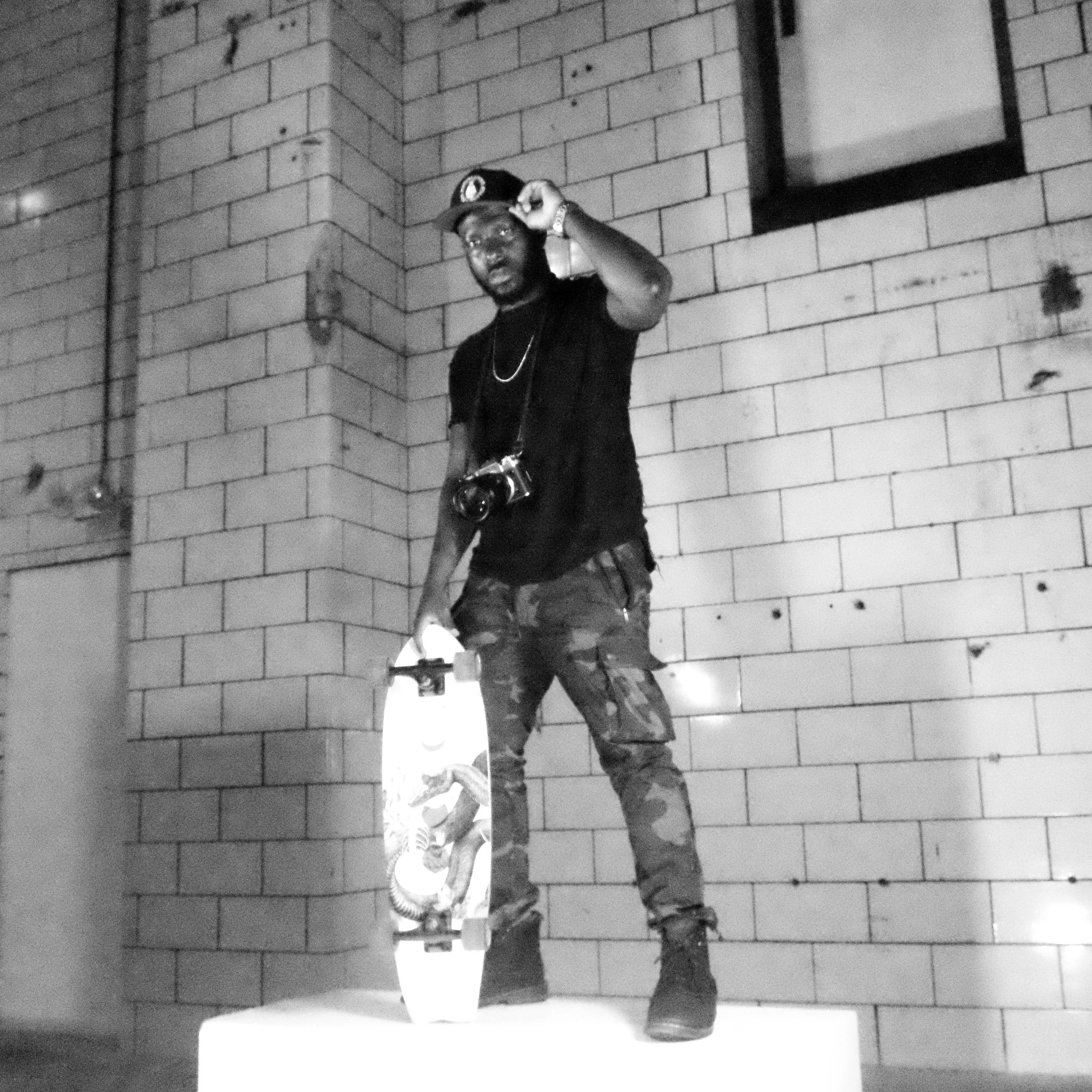

I could imagine the din of the presses as they printed the daily news, but our voices echoed and fell off the empty tiled walls. When I was working, my husband saw something he couldn’t explain, watching us from the gangway above—a fleeting Southern Gothic moment. It was in this room that these black-and-white photos were shot.

These portraits are now part of The Hurricane Party Archive, a collection of art and ephemera curated by James Black, Scott Satterwhite, Neil Byrne, and Valerie George. They hope to preserve the Mobile underground music scene—hurricanes or not—for future generations.

JULIA GORTON

09.08.23, 09.09.23, 09.13.23, 09.14.23

04.19.24, 04.20.24 COMING SOON

PHOTO BY MATT O’BRIEN